Understanding Free and Opensource Operating Systems, The Technology and Philosophy Of - Chapter 1 - History of Linux and Unix

Chapter 1 - History of Linux and Unix

Objectives

- Explain the six phases of Unix/Linux maturity and how they encompass each generation’s technological changes

- Explain the contributions of Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie to Unix

- Explain the contributions of Richard Stallman to Unix, Linux, GNU, the FSF, and Free/Libre Software

- Explain the contributions of Linus Torvalds to the creation of Linux and the Linux Kernel

- Discuss the nature of modern commercial distributions of Linux and Unix operating systems

- Compare and Contrast the principles and key differences of Free/Libre Software and Opensource Software

- Discuss and explain how Free and Opensource software lead to Cloud Computing and Mobile Compute

Outcomes

At the completion of this chapter a student will understand and be able to explain the context in which Unix and Linux were created. You will be able to relate key names; Thompson, Ritchie, Stallman, and Torvalds to their respective technological contributions to free and opensource software. You will be able to explain what a Linux distribution is and how Free and Opensource software lead to modern compute paradigms such as Cloud and Mobile. This chapter will also discourse over 6 discreet technology phases since the create of the UNIX operating system.

In this chapter the terms Linux and Unix are generally interchangeable from a conceptual standpoint. For a large part of this book the conventions are the same - their history is intertwined. Though this book focuses on Linux we would be depriving you of the spectrum of free and opensource software if we left Unix and BSD out. If you are curious, the name is pronounced “Lin-ucks;” link to audio pronunciation, and Unix; “Yoo-nix.”

Zeroith Phase - Where it Began and Why it Matters Now

One could say that computer programming as we would recognize it started in the 1930’s with Alan Turing. Operating Systems that we would recognize such as Unix didn’t materialize until the early 1970’s. And desktop and server CPU and hardware architecture we are familiar with started in the 1990’s with Intel, and Mobile computing started in late 2000s using ARM based processors.

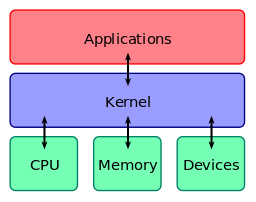

These modern operating systems such as Windows, MacOS, Ubuntu Linux, Fedora Linux, Android, and others all have a basic architecture in common. At a foundational level all operating systems have three basic components: the kernel, program languages and compiler tools, and user interface and user applications.

The Kernel 1

In the same way all plants require a seed or a kernel to grow, any computer operating system must contain a kernel. This is a small piece of code that forms the core of your operating system. You the user will not interact with the kernel, but devices you use, like a keyboard, mouse, touchscreen, or a Wi-Fi network card will do so when you take any action on the system. How do the devices talk to the kernel? They speak to the kernel via device drivers. The figure above describes a two way flow of data; the user interacts with the operating system and the operating system interacts with the kernel. The kernel is the hardware abstraction layer that handles all interfaces from the operating system to the hardware. Without the concept of device drivers and a kernel, each operating system would have to be custom built to communicate with the CPU. The majority of operating system code and drivers are built in the C language.

Take the Windows operating system for instance in which you have just one version, 7, 8, 10, etc. etc. How many of you have an AMD processor? Have an Intel processor? Or an ARM processor? What kind of network card or motherboard brand? You may not even know off the top of your head. There is no need to know because of the Windows kernel abstracting these differences away.

Programming Language and Compiler Tools

Once you have a kernel to interface with the hardware, you need a programming language and standard library that will let you build tools and libraries to put an operating system together. In Unix and Linux most system tools and commands are built using the C language. These tools such as gcc (GNU C Compiler) help you to compile and build other tools and programs.

User Interface and User Tools

All operating systems need a way for a user to interface with the kernel. This is where the shell and user applications (sometimes called user-land) come into play. The shell is a way for the user to send commands to the operating system–which executes these commands through the kernel and returns output to your screen. Unix originally didn’t have a graphical user interface but it always had a shell, which we will cover more about in chapter 5. Even when you click an icon in a GUI, it is actually issuing commands via the shell behind the scenes.

User tools include all tooling or commands (executable binaries) needed to function in an operating system: copy{.bash}, delete, move, make directory, kill a process, open a text editor to modify a file, issue a compile command to the C compiler, redirect output from the screen to a file, etc, etc. User applications like web browsers and email clients are seen as user-created tooling that is an amalgamation of many smaller tools to accomplish a larger task.

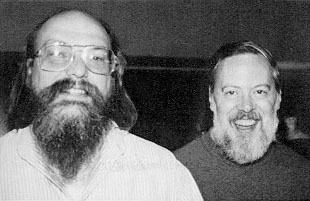

Ken Thompson, Dennis Ritchie, and Bell Labs

Many people supported and worked on what would become known as the Unix operating system but two names have received most of the credit for the creation, promotion, and use of Unix: Know these names!

Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie

Without Thompson and Ritchie2, there would be no Unix and most likely no Linux today. Until recently both were employed as Distinguished Engineers at Google. Dennis Ritchie passed away in 2011 (same year as Steve Jobs). Ken Thompson is still working and recently helped produce the Go programming language while at Google.

To begin this story we need to go back to 1968. At the time, the combined might of all the brightest minds of General Electric, MIT, ARPA, and Bell Labs came together to try to build a multi-user operating system called MULTICS. Now today those aren’t names that come to mind when you think of computer companies. Yet in 1968/1969 General Electric and the government (ARPA) were the large funders and suppliers of computing (The PC market we know of today doesn’t come into existence until 1984!).

Bell Labs at the time was basically the idea shop of the United States–where the best and brightest went to invent everything we take for granted today. Bell Labs was spun off by AT&T and became Lucent Technologies, which became Alcatel-Lucent and now is owned by Nokia. One could argue that Google, Netflix, and Facebook have taken its place where the brightest minds go to invent new things in America. No wonder that Dennis Ritchie, Ken Thompson, Brian Kernighan and even James Gosling (creator of the Java programming language) are and were employees at Google.

Like all projects that try to do too much, MULTICS stalled in gridlock between the different companies and the demands of the government. This left one crafty engineer with free time and (for those days) a true rarity - unused computers; PDP-7s to be exact. Ken Thompson had an insiders view of the innovative things MULTICS was trying to accomplish and why the inner workings of the MULTICS project went wrong. Thompson also had a job to do as a Bell Labs researcher. On his own time, he began to use these PDP-7s and program his own multi-user operating system, but with a different twist. It was designed by him, and solved daily work and coding problems he had.

In 1969-70, the “Unix” concept had never been attempted. Thompson had no idea that his pet work project was going to become part of a computing revolution. Whereas MULTICS and other computer systems were designed by committees and based on marketable features–due to the nature of the up front financial investment, Unix was simple and easy to build because it solved only a small set of problems–which turned out to be the same problems every engineer had. The overall reason that Unix took hold was that it was designed by engineers to solve other problems that engineers were having–enabling them to get work done.

Unix differences from existing commercial Operating Systems

- Written by Ken Thompson on his spare time

- No company owned it or committee designed it for commercial purposes

- Built by engineers

- Solved problems that engineers had

- Had a consistent design philosophy

- Designed to be portable and work on many hardware vendor platforms

Thompson’s Unix success was also a byproduct of its main design philosophy:

- Everything is a file

- This means that everything can be read from or written to: all the way from devices to text files

- Unix is portable

- Tools and OS code can be recompiled for different environments because everything is written in C.

- I/O is redirectable between small executables

- Small tools that do one and only one thing well

- Output of one command becomes the input of another command.

-

Complex applications are built by chaining the output of small executables together with pipes -> “ ”

The best demonstration of these tenets was during a coding challenge issued by Jon Bently in 1986 to:

Read a file of text, determine the n most frequently used words, and print out a sorted list of those words along with their frequencies.

There were two answers to the problem. Donald Knuth a preeminent computer scientist, called the “father of analysis algorithms” tackled the problem by originating an ingenious new programming language, lengthy documentation, and code to solve the problem. Comparatively, Doug McIlroy, who was Thompson and Ritchie’s manager, wrote a six line Unix shell script to do the same work Knuth did in his massive work. We will talk more about Doug McIlroy and his contributions to Unix in chapter 6. Here is his answer:

tr -cs A-Za-z '\n' |

tr A-Z a-z |

sort |

uniq -c |

sort -rn |

sed ${1}q

PDP-7

Between 1970 and 1974 Unix grew from a pet project into a real product and one of its crowning achievements–its portability across hardware came to life. Unix was originally written in assembly language for the PDP-7. Its code needed to be as low level as possible because disk storage space was a HUGE problem in those days. The code was good and highly optimized, but the problem with writing in low level assembly is that the code is optimized to only run on a PDP-7 system in this instance. Not on a PDP-11 or a DEC VAX, or an IBM 360, etc, etc.

So what you gain in efficiency you lose in portability. What good would it have been if Unix could only be used on a PDP-73? It would have stayed a Bell Labs pet project and become an obscure entry on a Wikipedia page today.

While Thompson was building Unix to solve his own workloads, his fellow engineers at Bell Labs got wind of what he was doing and asked to have access to his system. These new people contributed additional functionality to solve their work problems. Enter Dennis Ritchie, who championed Ken Thompson’s Unix in Bell Labs. Ritchie was a computer language creator and saw the utility of Thompson’s Unix, but realized it was trapped by its use of PDP-7 assembler language. Today we take for granted high level programming languages like C, C++, Python, and Java. In the early 1970’s none of these languages existed.

Ritchie’s initial work at Bell Labs was on a high level programming language that could would allow a user to write one piece of code and compile it on different computer architectures. In 1970 this was generally not possible and a radical idea. His initial work was on a language called “B” which was derived from a language called BCPL. B was designed to execute applications and operating system specific tasks but didn’t handle numeric data (a feature designed to save precious hard drive space). B was also missing other features you would expect in a modern programming language.

The next logical step was that Thompson and Ritchie went to work extending “B” with all the features they would need to make an operating system fully function and portable. They called this language surprisingly, “C” – the same “C” language you know today. C was different from assembler in that it resembled assembler code syntax but a high enough level of abstraction that the “C” code was an independent language. With the advent of C - Unix was rewritten in this language. With the creation of C compilers for different hardware, Unix could now be built and be recompiled on different architectures, PDP-7, PDP-11, DEC VAX, DEC Alpha, IBM 360, Sun SPARC, eventually Intel and x86, etc, etc.

Assembler and C Language Comparison

Hello World in x86 Intel Assembly for Linux.

section .data

msg db "Hello World!",0x0a

len equ $-msg

section .text

global _start

_start:

mov ebx,0x01

mov ecx,msg

mov edx,len

mov eax,0x04

int 0x80

mov ebx,0x00

mov eax,0x01

int 0x80

Hello World in x86_64 Intel Assembly for Linux

hello:

.string "Hello world!\n"

.globl _start

_start:

# write(1, hello, 13)

mov $1, %rdi

mov $hello, %rsi

mov $13, %rdx

mov $1, %rax

syscall

# _exit(0)

xor %rdi, %rdi

mov $60, %rax

syscall

C Language equivalent of above code

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("Hello, world!");

}

Since Ritchie had created “C” to solve all the problems Unix had, it became the de facto language of Unix and from that point on pretty much all operating systems were written in “C” after Thompson and Ritchie showed that you could use a high level language to make Unix portable across many platforms. Recently a project to restore the original UNIX assembly code from a tape and documents recovered from 1972 has begun and is hosted on Google code.

Brian Kernighan

Thompson didn’t have a name for his project initially, another related figure, Brian Kernighan4, can be credited with giving it the name UNIX. This was a play on words–MULTI vs UNI in the name. Kernighan also helped write the original C language textbook along with Dennis Ritchie (Published in 1978, called K&R C which some of you might have used when in school).

First Phase of Unix Maturity – OS Implementation

By 1974/75 internal use of Unix at Bell Labs was high amongst engineers. Word was starting to spread about it as Bell Labs engineers moved on and into academia. Other Bell Labs divisions and universities got wind of this and began to request Unix install “tapes” for their own use. Tapes meant giant mounted magnetic tape reels that contained all the operating system code. By law AT&T was prohibited from getting into the computer business so they took a hands-off approach to Unix at the time. AT&T left it curiously as Thompson and Ritchie’s pet project. Many universities at this time, wanting to teach computing and operating systems, began to request copies of Unix to teach in their Operating Systems classes. This was attractive to universities because Unix was a fully operational and working system but the main draw was that the source code was freely given away by Ken Thompson. You sent him a letter, paid for shipping, and you got a magnetic tape reel within a week or so. Thompson had no concept of “ownership” and freely shared his project with anyone who was interested. One could say this was Free Software a decade before the term was coined.

In 1975 Ken Thompson took a sabbatical from Bell Labs and went back to his Alma Mater, Berkeley, in California. Installing the Version 6 Unix Release, the students at Berkeley started adding their own features to improve it to solve their own problems. One student in 1978, Bill Joy, added the vi editor and the C Shell (two things still in use today in modern Linux and Unix) and people started referring to the changes made to Unix at Berkeley as BSD Unix (Berkeley Software Distribution Unix).

By 1980, with many copies of Thompson’s Unix now in circulation and nearly a decade of work there started to be fragmentation of the original Unix. At this time the Berkeley Software Distribution of Unix was beginning to vary widely in functionality and quality from commercial AT&T UNIX. Since the code was technically proprietary under AT&T’s ownership there was no way to contribute code back to AT&T. Another interesting problem AT&T had was that by the end of the 70’s all those students who had learned Unix in college went to work in corporations and began to request Unix to be used as their corporate hardware platforms.

Now AT&T had a financial motive to commercialize Unix. In 1982 AT&T released Unix System III, followed by System V in 1983, as a commercial product for sale to companies, while offering a restrictive derivative license for universities. By the dawn of the 1980s the first phase of Unix maturity was complete. The operating system, its code, and its design philosophy were well proven and in wide use across universities and commercial enterprises. In the 1980s the focus of Unix takes a dramatic shift towards application creation.

Second Phase of Unix Maturity – Unix Users, Application Development, and Licensing

The next phase of Unix history revolves around the important work done by developers to create applications and standards around the Unix operating system to increase productivity and accessibility. There are many people who contributed to this phase but among the names we will discuss there is none more important than Richard Stallman, also known as RMS.

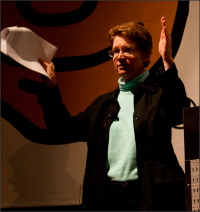

Richard Stallman and GNU

Richard Stallman5 was a researcher at MIT in the early 1980’s. He was part of what you would call today a “hacker culture” that was constantly researching and developing new tools and applications. They were explorers eager to solve problems and this lab had a strong culture of sharing software and ideas amongst its students, faculty, and employees. By 1984 a number of small events began to erode this free environment. One such issue was the introduction of account passwords for every computer user. We take passwords for granted these days, but in the early 1980s they weren’t standard issue and the implementation of them seemed draconian to users who had always used computers without passwords–freely.

Another event which bothered Richard Stallman was the removal of the capability to modify a network printer’s firmware to send an email in case of a paper jam. This was a problem as their networked printer was 2 floors up from the lab and involved quite a walk. The original printer allowed access to their firmware code and Richard Stallman improved the code and added a feature to send emails when a paper jam occurred. The next version of the printer prevented the users from inspecting the firmware and modifying the code–hence locking the lab into a proprietary device. Worse–there was no mechanism for the lab to contribute its improvement to the printer software back to the company.

Stallman disagreed with these concepts as they hindered the ability of the users to inspect the code and improve it, and share those improvements, and suit the software to serve their needs. By 1983 Stallman began to argue that the user’s software freedoms were being trampled upon. To make matters worse, in 1984 AT&T began to withhold the source code of Unix and restricted the access of those in the academic world to be able to work with the AT&T source code. Users were now beholden to the closed nature of the products they were using–even if they had paid for the software. Stallman saw this as a moral injustice and set about making it his life’s work to rectify this issue.

The GNU Manifesto

By late 83/84 Stallman’s desire to see free/libre software became a manifesto–an open declaration against proprietary code. This manifesto aimed to reverse engineer all the functionality, capability, and tooling of the then popular Unix operating system BUT without the proprietary and restrictive licenses that commercial Unix operating systems entailed, thereby giving the world access to a free (as in freedom) operating system. He would call it GNU (guh-noo) or GNU’s Not Unix. Everything done under the GNU project would have the source code free for analysis, study, modification, and redistribution. Stallman always intended free software to fight perceived injustices relating to software. The term free software has nothing to do with cost or money. Through the manifesto, Stallman wanted to let people know his project was Unix-like in functionality and operation and free as in freedom in relation to the source code and redistribution of it.

He felt strongly enough to announce the GNU project publicly in the fall of 1983, and to quit his job working in the MIT lab in 1984 to avoid conflict of interests in pursuit of this work. The GNU Manifesto was officially published on October 3rd, 1985 and issued a general call to free software arms. Here is the opening paragraph from the manifesto:

Why I Must Write GNU

“I consider that the Golden Rule requires that if I like a program I must share it with other people who like it. Software sellers want to divide the users and conquer them, making each user agree not to share with others. I refuse to break solidarity with other users in this way. I cannot in good conscience sign a nondisclosure agreement or a software license agreement. For years I worked within the Artificial Intelligence Lab to resist such tendencies and other inhospitalities, but eventually they had gone too far: I could not remain in an institution where such things are done for me against my will.”

It is easy to write a manifesto but hard to lead a revolution they say. Stallman was one of those rare minds that could do both; a brilliant programmer who had the will and the raw skills and capability to build an entire operating system from scratch and give it away for free and he would get almost all the way there.

“So that I can continue to use computers without dishonor, I have decided to put together a sufficient body of free software so that I will be able to get along without any software that is not free. I have resigned from the AI Lab to deny MIT any legal excuse to prevent me from giving GNU away.”

Free Software Foundation and the GPL

In late 1985 the FSF – Free Software Foundation, was formed to be the holder of all the intellectual property of the GNU project with the motto:

“Our mission is to preserve, protect and promote the freedom to use, study, copy, modify, and redistribute computer software, and to defend the rights of Free Software users.”

With this, they wrote the GPL - GNU Public License, which is a legally enforceable copyleft license. Copyleft is a play on the word copyright, where a copyright restricts the rights of a user. Copyleft, on the other hand enshrines and enforces certain rights to the user of the software. The 4 software freedoms that the GPL licensed software enshrines are:

0) the freedom to use the software for any purpose 1) the freedom to change the software to suit your needs 2) the freedom to share the software with your friends and neighbors 3) the freedom to share the changes you make

In using the term “Free software,” it means software that respects users’ freedom and community. Roughly, it means that the users have the freedom to run, copy, distribute, study, change and improve the software. Thus, “free software” is a matter of liberty, not price. To understand the concept, you should think of “free” as in “free speech,” not as in “free beer”. We sometimes call it “libre software,” borrowing the French or Spanish word for “free” as in freedom, to show we do not mean the software is gratis6. You can see a really clear 10 minute presentation of the meaning of Free Software by Richard Stallman at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPPikY3uLIQ.

GCC, BASH, and GNU Coretools

In 1984 RMS started his work of creating a free Unix-like operating system. Since Unix was built upon the C programming language, the first thing needed to build a kernel, a shell, or any tooling was a C compiler. This project was called GCC (GNU C Compiler) which was a “free” version of the proprietary Unix AT&T cc program (C Compiler).

After GCC was finished, Stallman could begin to build other tools with this free C compiler. He needed an extensible text editor to edit files and with which to run GCC to build software. A few years prior, in 1981, James Gosling had created the Gosling Emacs editor; gmacs. We will learn more about editors in chapter 7. This name should be familiar because James Gosling would later go on to create the Java programming language while at Sun in 1994. Stallman almost single-handedly rewrote all of Gosling’s code to produce a “free” version of gmacs which he called GNU Emacs. This program is over 30 years old and still in use and active development to this day.

The next step the GNU project took was to begin reverse engineering all the basic Unix tools and commands needed to accomplish tasks: such as ls, grep, awk, mv, make and cp. Eventually an entire “zoo” of projects was created and are available at GNU Project website. Other GNU tools were added by contributors and volunteers over the years. By 1991 the GNU Bash shell was completed. A shell is the way the user interacts with the operating system to issue command. This was the last major tool that needed completing to have an entire function free Unix-like operating system.

The GNU project did remarkably well in quality and quantity of free programs considering there were created mostly by volunteers with little funding and no corporate backing. They had pretty much reverse engineered, and in some cases improved, all the components of AT&T Unix by 1991 (8 years of work). The last thing the project was missing was the most critical piece… they didn’t have a kernel for their operating system. Turns out that writing a kernel is much harder than it looks.

GNU Hurd – The Kernel That Was Not to Be

In their grand ambitions the GNU project was started in 1985 to create a kernel for the soon to come GNU operating system called GNU Hurd. The name GNU Hurd is also another clever recursive hack, as the name GNU has a double meaning. There is a large goat like animal called a gnu, which lives in herds that roam the plains of Africa. The name Hurd came from the similarities of a herd of animals and the design of the GNU Kernel would be a “herd” of small micro-processes communicating together, like a herd of gnus (the animal). It seems that GNU developers really love clever hacks. It it something that you have to get used to in opensource as the spirit of bad puns and clever hacks has carried on to this day.

Hurd made some false starts in its initial micro-kernel development phase causing multiple versions to be created and scrapped. What they were trying to do was really innovative but really complicated and difficult to make work reliably. In retrospect Hurd was never finished. By 1998 The GNU project had all but stopped active development and promotion of GNU Hurd as the kernel for its free operating system. The GNU project realized that the Linux Kernel had accomplished in four years what GNU had spent 13 years working on.

GNU Hurd still exists and is in a usable alpha stage. It is downloadable today by joining it with the Debian Linux distribution applications–all GPL compliant mind you.

The GNU project instead recommends using the Linux kernel instead and joining the GNU tools with it to form GNU/Linux. In some ways, this realized Stallman’s dream of a free operating system and yet his greatest disappointment would be that Linus Torvalds delivered the necessary operating system kernel and not the GNU project. By 1991 a new name comes onto the scene, Linus Torvalds and the Linux kernel come along and make the next leap in the free and opensource operating system world by introducing the Linux kernel.

Free and Opensource State in the 1990s

Professor Andrew Tanenbaum and Minix

Before we talk about the Linux kernel, we need to talk about the state of other free and opensource operating systems at this time. One in particular is worth mentioning: the Minix operating system. With the closing off of the AT&T Unix source code in 1984, academics and university researchers were left without source code to show as examples in classes.

Professor Tanenbaum 7 was teaching at Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam - and began to write and implement his own free Unix-like operating system initially for teaching and research purposes. It was 12,000 lines of C code and system call compatible with commercial Unix. The name Minix was a combination of “minimal” and “Unix.” Minix 1.0 and 1.5 were released in 1987 and 1991 respectively. Minix 1.0 and 1.5 were freely available to anyone as the source code came in the appendix to a textbook about operating systems written by Tanenbaum in 1987. Minix was designed to run on older x86 Intel processors (286 and 386 systems) and in version Minix 1.5 a port was included for Sun SPARC processors.

SPARC workstations were common desktop stations used by students and researchers in universities at that time. Any enterprising student could find and old 286 PC or old Sun SPARCstation to run Minix on. The source code for Minix 3 is currently available in a Git repository and is still being developed and researched. In 1991 many people believed that Minix could have been a viable alternative to commercial Unix and become the still missing GNU Hurd kernel. But the Minix creator, Professor Tanenbaum, was not interested in moving into competition: the code was nowhere near as mature as the Unix code base, which by 1991 had been in existence for almost 20 years! Minix appeared on the radar but was not the missing piece to the GNU puzzle.

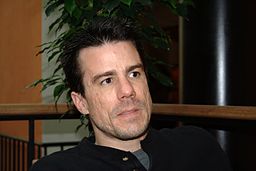

Linus Torvalds and Linux

In 1991, Linus Torvalds was a graduate student at the University of Helsinki in Finland. As a student Torvalds was using Unix for his courses on the university’s Sun SPARCstations. He was not pleased with Sun’s Unix, called SunOS, but felt it was the best of the commercial Unix available. His real dream was to run his own Unix-like operating system on his own personal PC. He had recently purchased an Intel 386 processor based desktop PC. Linus tried using Minix, but was put off by its minimalist approach and realized it had some good design concepts but was not a complete Unix replacement. In a fashion not unlike Ken Thompson, Torvalds set out in the early part of 1991 to see if he could build his own kernel for his own operating system for his own use and purpose that was Unix-like but wasn’t Minix.

This was very impressive feat for a single person. Torvalds himself acknowledged that if GNU Hurd had been ready for production or if at this time AT&T hadn’t been suing BSD, he would have re-used their kernel work and not built his own. By August 25th of 1991 the initial release of the Linux kernel was posted online8. The quote from the beginning of the chapter was the basis of the initial post to the Minix Usenet Newsgroup(A newsgroup was a bulletin board-like precursor to the actual Internet - like Google Groups in a sense–today you would use Twitter). His initial work was not quite a full-fledged system but really just a small kernel, with a port of the GNU Bash shell, and a port of the GNU C Compiler (GCC). Many things were missing, support for other processors, audio, printers, etc etc but it was like a crack in a damn - something was about to burst forth in the operating system world.

By September of 1991 Linux kernel version 0.01 had been posted to the University of Helsinki FTP servers for public download. The initial kernel included this release note by Linus:

“Sadly, a kernel by itself gets you nowhere. To get a working system you need a shell, compilers, a library etc. These are separate parts and may be under a stricter (or even looser) copyright. Most of the tools used with Linux are GNU software and are under the GNU copyleft. These tools aren’t in the distribution - ask me (or GNU) for more info.”

By February of 1992 Linux 0.12 kernel had been released. As more users began to download and use Linux, Linus decided to give the project a proper license for its use. Having seen Richard Stallman speak at the University of Helsinki a few years prior, Linus was inspired and decided to release the Linux Kernel under the GPLv2 license. This was the smartest thing anyone could have done and no one could have foresaw the great economic value the Linux kernel and GNU tools licensed under the GPL has generated for many companies. This combination allowed Google to start and grow to its tremendous size. This combination allowed companies such as Amazon, Yahoo, and Google to get a tremendous start by allowing them to customize the Linux operating system not having to place precious startup capital into Unix licenses.

The reason why Linux is so popular is because of this fledgling kernel that worked enough for people to use, hack on, build upon, and improve now had a governance structure with the GPL that could accept code contributions and be available for commercial work as well. Being GPL the Linux kernel was instantly compatible with all of the entire GNU project’s tools base. You instantly had the kernel that GNU was missing and the Linux kernel had all the tools and applications it needed to be usable.

People began downloading and compiling the Linux kernel, adding the GNU tools, and making fully capable Unix-like operating systems for personal use soon after commercial use. Linus’ brilliance comes not from ingenuity but comes from good engineering principals like knowing when not to go down dead-end development trails. Torvalds’ work was not perfect but was good enough that others could take it and start to use it and improve upon it. From 1992 to 2001 the Linux kernel grew rapidly in size and features and spawned commercial companies to sell and support Linux Distributions. Stallman’s dream of a complete free and opensource operating system was being realized.

This should have been cause for great celebration amongst the Linux and GNU communities. The FSF saw this as a victory for GNU and began calling the system GNU/Linux, assuming that without the GNU tools, the Linux kernel would be useless. The FSF assumed credit in this case. But Linus Torvalds didn’t see it that way. He just referred to the system as Linux. He just ignored the FSF’s requests and people referred to what should have been GNU/Linux as just Linux, leaving the GNU part out even though all of their tooling is what made Linux possible. In a sense that is Linus’ unique personality. On the other hand, Richard Stallman will not conduct any interview unless there is an agreement to only use the term GNU/Linux not Linux. Some would argue that this is Stallman’s ego, but he insists he only wants credit where credit is due. This issue is still a matter of contention for the FSF today. Richard Stallman resigned the presidency of the FSF in September of 2019 and has been replaced by Professor Geoffrey Knauth.

Linux Kernel Attributes Compared to Unix OS Attributes

Creation Method

- Linus Torvalds as a graduate student at a university because of his curiosity

- Thompson and Ritchie developed as Bell Labs Engineers to solve computer problems

Release Cycle

- Linux releases a new kernel in short windows and maintains an LTS, Long Term Support Kernel version as well

- Linux distributions have to plan around this and choose which kernel to use.

- Unix/BSD maintain a complete operating system and release everything together in a 1 to 2 year cycle

License

- The Linux kernel is licensed and protected under the GPLv2 and allows individuals and corporations alike to contribute back to the Linux kernel, but source code must be open and freely available.

- Each BSD project is licensed under a permissive license which allows for derivative works to be made without requiring that the source code be given back to the main project. BSD distros do take outside contributions.

- Commercial Unix does not take outside contributions

Tooling

- Any Linux based operating system need to make use of a set of coretools – usually the GNU coretools to be able to function

- BSD/Unix may use some GNU coretools but has their own versions internally built in with the distro

Linus’ Personality

Some people think Linus’ personality is a shtick or a comedy act he puts on. But whatever it is he is very straight forward in dealing with people, and will not spare anyone a harsh public rebuking if he thinks they made a sloppy mistake. He justifies this as kernel work is hard and you need to be prepared to take difficult criticism if you are going to survive here. Some consider Linus really mean and even aggressively mean spirited to those with whom he has disagreements. When approached about this, originally Linus states that he only cares about the kernel and no one else matters to him. These links below provide some points and counter points about Linus.

On September 16, 2018, Linus Torvalds issued a public apology for his past behavior and temporarily stepped down as Linux Kernel maintainer. You can read the apology letter on the Kernel mailing list. Some say the apology wasn’t needed, some say it is too little too late. Others wonder if a man of Linus’ age (48) can be reformed. Some see this as a step in the right direction and offer a chance for redemption, some would prefer him never to return. This opens a bigger question of can someone’s sins that are on the internet ever be forgiven?

In October 2018, Linus Torvalds returned from his one month of reflection. He realized that his original focus had made the Linux Kernel development area difficult for new people. Torvalds said, “I need to change some of my behavior, and I want to apologize to the people that my personal behavior hurt and possibly drove away from kernel development.” In addition a Contributor Covenant was added to the Linux Project to govern these kinds of interactions in the future.

AT&T and BSD Lawsuit

The nascent Linux project saw a rush of growth and developer contribution from August of 1991 to February of 1992. But where did all these developers come from? At this time we need to go back to Berkeley University and check in on the BSD project, (Berkeley Software Distribution). In the late 80s and up to the early 1990s BSD Unix development had been flourishing at Berkeley. Some would attribute this to great minds and an open environment, some would attribute it to lots of government funding. Either way the product produced began to eclipse the commercial AT&T Unix in features and quality. BSD began to significantly and irreconcilably differ from AT&T Unix.

AT&T seeing this decided in the early 1992 to take the BSD project to court in order to stop BSD from cutting into their commercial business. BSD technically came from AT&T Unix back in 1976, when Ken Thompson took his sabbatical at Berkeley and brought the then pet project AT&T Unix with him. AT&T found that some of the BSD code had not been changed as was claimed and was still original AT&T Unix code, which they claimed was a copyright infringement. In early 1992 AT&T was granted a court ordered development injunction against the BSD project, preventing development work from being done on BSD Unix. This was the perfect time for Linux kernel development to flourish, protected by the GPL, there were no licensing or copyright issues to worry about. BSD developers in droves flocked to the Linux project. By the time the lawsuit was finished in late 1993/1994 it was too late. The results of the court case were that BSD could no longer use the term Unix to describe itself and they had to rewrite a handful of programs to remove AT&T code. AT&T had succeeded in planting the seed for the growth of the entire Linux industry with this action. The Linux rocket had left the launch pad.

After the BSD and AT&T lawsuit was settled the BSD code base split into three and then four main distribution families–each with their own focus but all common enough to share code between them. Also they are free of any contention with commercially licensed Unix and usable for enterprise work. Unlike Linux, BSD lacks a major corporate sponsored distribution, like Ubuntu or Red Hat. All are maintained by volunteer organizations.

- FreeBSD

- DragonFlyBSD, split from FreeBSD

- NetBSD

- OpenBSD, split from NetBSD

Third Phase of Unix Maturity - Free and Opensource Software Enters the Enterprise

Free Software vs. Opensource Software

By the end of the 90s a curious thing was happening; Microsoft had a near total domination of the desktop PC operating system market and was being investigated by the US Department of Justice for anti-competitive practices. Apple had just brought Steve Jobs back as CEO and was beginning to take steps towards recovering from lost decade. The Internet as the phenomena we recognize today was just beginning to take root in homes across America through dialup services like AOL, Compuserve, and Prodigy. At the same time, the quality and quantity of free and opensource software was increasing. The Internet was being powered by webservers and databases. Opensource tools such as the Apache Webserver, Perl programming Language, and MySQL database became the killer apps to use on Linux or BSD.

The term opensource software is pervasive today but until 1998, it didn’t exist–they were still using the term free software. The term free software had existed since 1985, but because of the ambiguity of the English word free it became associated with zero-cost free and not freedom free. The term free can also give the potential idea of cheap or shoddy work–compared to professional proprietary work and the enterprise would not touch it.

The term opensource was not a movement away from the principles of free software but a chance to show the enterprise that the opensource development model was sustainable and could produce superior products. To better understand the difference and how it impacts us today, we need to meet some of the key players.

Christine Peterson

Christine Peterson9 was a technologist who was part of the group that would become the OpenSource Initiative. She is generally credited with coining the term, “Opensource,” as a differentiator from “Free Software”.

Eric S. Raymond

Eric S. Raymond10 had long been a free software developer and part of the hacker community. Raymond’s most famous contribution to opensource is writing a seminal paper that was later reprinted in book form called, “The Cathedral and the Bazaar”

His main point was that by business-as-usual practices Linux should have been a massive failure and a poorly implemented experiment. But instead it was an unprecedented success because of the opensource development method. His article examined why this is the case comparing the cathedral like design of Emacs and GCC–open but not publicly available during development versus Linux bazaar style development of everything publicly open and available at all time via the internet.

In conclusion Raymond proposed that opensource code and an opensource design methodology of treating your user as a valued resource was vital to an opensource project’s success. Based on this Raymond and Bruce Perens founded the Open Source Initiative (OSI) and were part of the group that in 1998 coined the term “opensource”. Their goal was to continue to promote free software but instead of focusing on the moral issue of software freedom, they focused on the design principals of producing superior software. A quote from Raymond puts his opinion bluntly;

As head of the Open Source Initiative, he (Raymond) argued that advocates should focus on the potential for better products. “The “very seductive” moral and ethical rhetoric of Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation fails, he said, “not because his principles are wrong, but because that kind of language … simply does not persuade anybody”. Eric S. Raymond

The “Cathedral and the Bazaar” was influential in helping the Netscape Corporation opensource their Netscape Web Browser code before the company was sold to AOL, under the name of the Mozilla project. This code gave rise to what would eventually become the Firefox web browser in 2002–thanks to Raymond’s writings.

Richard Stallman and the FSF alleged the OSI was willing to make freedom compromises in order to make larger productivity gains with opensource software and fired back in his article “Open Source Misses the Point”. The terms do overlap, but Free Software and opensource ultimately have two divergent meanings and free software is not opensource software.

There has been some compromise between the two camps by using the term FLOSS, Free, Libre, and Open Source Software, but the FSF does not recommend any licensing that allows a user’s freedom to be restricted. One way to conceptualize the difference would be to look at the concept of DRM software, which is basically the copy protection schemes on DVDs and digital music downloads. The OSI group would not be opposed to build opensource DRM software. But the FSF would be opposed to the entire concept of DRM–which is a tool they believe restricts a user’s freedom to play their DVD anywhere and in any way.

You can read Raymond’s two seminal books on Unix and opensource philosophy online as they are free and opensource licensed:

Opensource Software Definition

Open source doesn’t just mean access to the source code. According to the Opensource Initiative written by Bruce Perens, the now 10 rights enshrined in the OSD encompass the 4 software freedoms and extend them with a focus on applications in the business world. The distribution terms of open-source software must comply with the following criteria:

- Free Redistribution i) The license shall not restrict any party from selling or giving away the software as a component of an aggregate software distribution containing programs from several different sources. The license shall not require a royalty or other fee for such sale.

- Source Code i) The program must include source code, and must allow distribution in source code as well as compiled form. Where some form of a product is not distributed with source code, there must be a well-publicized means of obtaining the source code for no more than a reasonable reproduction cost, preferably downloading via the Internet without charge. The source code must be the preferred form in which a programmer would modify the program. Deliberately obfuscated source code is not allowed. Intermediate forms such as the output of a preprocessor or translator are not allowed.

- Derived Works i) The license must allow modifications and derived works, and must allow them to be distributed under the same terms as the license of the original software.

- Integrity of The Author’s Source Code i) The license may restrict source-code from being distributed in modified form only if the license allows the distribution of “patch files” with the source code for the purpose of modifying the program at build time. The license must explicitly permit distribution of software built from modified source code. The license may require derived works to carry a different name or version number from the original software.

- No Discrimination Against Persons or Groups i) The license must not discriminate against any person or group of persons.

- No Discrimination Against Fields of Endeavor i) The license must not restrict anyone from making use of the program in a specific field of endeavor. For example, it may not restrict the program from being used in a business, or from being used for genetic research.

- Distribution of License i) The rights attached to the program must apply to all to whom the program is redistributed without the need for execution of an additional license by those parties.

- License Must Not Be Specific to a Product i) The rights attached to the program must not depend on the program’s being part of a particular software distribution. If the program is extracted from that distribution and used or distributed within the terms of the program’s license, all parties to whom the program is redistributed should have the same rights as those that are granted in conjunction with the original software distribution.

- License Must Not Restrict Other Software i) The license must not place restrictions on other software that is distributed along with the licensed software. For example, the license must not insist that all other programs distributed on the same medium must be open-source software.

- License Must Be Technology-Neutral i) No provision of the license may be predicated on any individual technology or style of interface.

Opensource Licensing

The creators of the Opensource initiative (OSI) took a different approach to market free software not as a moral issue, but as a development improvement and business use case. This lead to the creation of similar licenses to the GPL, but what was termed as weak copyleft or as the Free Software Foundation calls them, Pushover Copyleft. These licenses allow for contributions back to the creators as well as the ability to use, share, and inspect the code. They provide one key additional feature in that they let you make a copy and keep the changes–making them proprietary. GitHub has created a site to help you choose a license for your software called, “Choose a License.”.

- MIT

- APACHE Public License 2.0

- BSD 3 Clause

- BSD 2 Clause or FreeBSD license

- ISC License

- MPLv2 - Mozilla Public License

- CDDL

- OSI Popular licenses

In addition there is the Creative Commons (CC which covers works that are not considered code. Writings and music are covered by Creative Commons, including all of Wikipedia. Creative Commons has a variety of options you can include that allow for remixing and redistribution or no distribution. There are options that allow for commercial redistribution or prevent it. There are provisions to make sure are credited, and others that are permissive. This way you can choose how your work will be used and contribute to the “Commons.”

Fourth Phase of Unix Maturity - The Rise of Commercial Linux

As the 1990s came to a close we began to see established companies adopting and using opensource projects in the enterprise, such as MySQL for database and GCC as a C/C++ compiler. Especially we begin to see companies trying to make commercial distributions of Linux by adding the GNU core utils and a GUI interface. Of all the Linux companies that started by the turn of the century, Red Hat Linux is one of the few remaining and by far the most successful. How successful? To illustrate this, as of August 10th 2015, Red Hat Linux has a market cap of ~14 billion dollars. Most of the Linux distributions started pre-2003 no longer exist.

Modern Linux Distributions

As the new century dawned, Stallman’s dream for the GNU operating system had become a reality. Companies were combining the opensource Linux kernel with the free GNU core utils, and by integrating GUIs such as X11, KDE, and the GNU GNOME project, they were creating what could easily be described as a GNU/Linux based operating system. Each company made their own Linux distribution, also known as a distro. As distributions began to proliferate, each distribution began to spawn flavors, derivatives, and different spins as well.

It is curious to see that there were a few small commercial BSD distributions at the same time, but none of them rose to prominence. One might wonder if, without the financial backing of a commercial entity, could a distro ever rise beyond a niche use? BSD distros would argue that mass commercialization was never their primary goal.

As of 2020, we have almost 28 years of Linux Kernel and Linux distribution work. Current major commercial Linux distributions hail from two primary and distinct families: Debian and Red Hat. For the purposes of this book I will focus on these two main distribution families. You can find almost all known Linux distributions at http://distrowatch.com.

The Debian-based Family

“I founded Debian in 1993. Debian was one of the first Linux distributions and also one of the most successful and influential open source projects ever launched. Debian pioneered a number of ideas commonplace today, including employing an open community that allowed (and encouraged!) anyone to contribute (much like how Wikipedia would later operate). And, with its integrated software repositories anyone could contribute to, Debian arguably had the industry’s first (albeit primitive) “App Store”. Today, more than 1,000 people are involved in Debian development, and there are millions of Debian users worldwide.” - http://ianmurdock.com

Unfortunately on December 31st, 2015, Ian Murdock took his own brilliant life. Bruce Perens eulogized him in this post: https://perens.com/blog/2015/12/31/ian-murdock-dead/. His legacy lives on through the Debian family of distros, which contains 4 major sub-families11.

Debian

The Debian distribution (pronounced “dehb-ian” officially, but sometimes the stress is put on the first syllable and you will hear “dee-be-an”) was founded in 1993 By Ian Murdock and is unique for being one of the major non-commercially backed Linux distro still in existence. The current release is Debian 10. The Debian project has unique characteristics that were designed into the project from the very beginning. Many believe these features are the key to their long term success and usage across the Linux landscape as there are currently 122 major Debian based distros in existence according to distrowatch.com.

- Initial release schedule was yearly but as Debian project has grown now is two year release schedule

- It is the only major Linux distribution not backed by a corporation.

- Debian is an all volunteer project and organization–project leader is elected on a rotating basis

- Dedicated to protecting software rights and freedoms of users

- First major distribution to come with a software contract - stating what rights the project will guarantee to the user

- Debian supports free and opensource software as superior to closed source but will allow for closed source software/drivers to be installed by the user

- Supported at various times 11 different processor types giving it a wide install base

- The Debian project and its history can be found at:

Ubuntu

Ubuntu Linux is a unique distribution 12. It is entirely based on Debian. It is Debian repackaged with a focus on applications that “just work.” Around 2004, Mark Shuttleworth, the founder of Ubuntu, was unnerved that Windows had such a dominant position in the PC market. He had been a Debian developer, but felt that the lack of a corporate sponsor in some ways hindered Debian from catching market share from Windows. He set out to make a Debian based distro which he called Ubuntu. Shuttleworth is from South Africa and Ubuntu is a Zulu word meaning “community”. Shuttleworth wanted his Linux distro to be people friendly and work really well out of the box–like Windows.

In 2004 Red Hat, which had previously owned the desktop Linux market, decided to exit and focus on selling Linux based server operating systems to corporate entities. Red Hat felt there was little money to be made in that market where the code was given away freely. This left a void that Ubuntu rushed to fill and they did it well. By 2006, Mark Shuttleworth who had started the Thawte SSL security company, which was bought out by Verisign, took his money and invested 10 million dollars in the Ubuntu Foundation to subsidize the creation and maintenance of Ubuntu Linux.

What made Ubuntu so successful was that they forked the opensource work of rock-solid Debian and built on top of it by adding closed source code and user centered features that where necessary in order to make the best experience. They had a business in mind and have indeed captured the desktop Linux market. But one problem is they haven’t found a way to make much money off of their excellent product. Ubuntu has a 10 million dollar parachute in the form of the Ubuntu Foundation which was seeded by Mark Shuttleworth 13. Shuttleworth formed a commercial company called Canonical that was formed to handle commercial support and hires the developers who work on Ubuntu. Ubuntu is commercially backed by Canonical.

Ubuntu pioneered the idea of rolling releases - releasing every 6 months. Each distribution is released in late April and late October so there are two distributions per year. Ubuntu also introduced the concept of an LTS, Long Term Support - this means that certain releases will have security patches, fixes, and software backported to it for 5 years, allowing you to base an enterprise business off of this product and assured system stability. The LTS releases happen every even year with the April distribution. So Ubuntu 16.04, 18.04, 20.04, 22.04 and so forth (the first number being the year).

PureOS

“PureOS is a general purpose operating system that is based on the Linux kernel and is focused on being an entirely Free (as in freedom) OS. It is officially endorsed by the Free Software Foundation. We adhere to the Debian Social Contract and the GNU FSDG.”

This is a Debian derivative, that has been produced with an FSF based focus on Free Software. In addition, the PureOS is being developed by Purism Company which develops Free and Hardware respecting privacy hardware as well as communication and cloud storage apps.

Devuan

Devuan Linux Project (Pronounced Dev-one) is a fork of the entire Debian project - not just a Debian based distro. This is a result of the “Debian Civil War” of early 2015 where in half of the Debian Project developers left the project to begin work on this distribution. It is a direct fork of the Debian 8.0 Jessie Code base with one major incompatible change to the core operating system; that cannot be merged back into Debian. The disagreement stemmed from Debian’s decision to implement Red Hat’s systemd init system over the old but reliable sysVInit. To change the core operating system is a monumental task and these volunteers undertook it and succeeded. The project started in August of 2016 and has now progressed to a stable systemd free Debian based release, Devuan 3.0. We will talk about this more in detail under the topic “Linux Civil War” later in this chapter.

Other Debian Based Distros

Some of the other notable Debian/Ubuntu based distros are as follows:

- Xubuntu

- Lubuntu

- Kubuntu Ubuntu remixed with the KDE desktop Environment

- MX Linux A midweight distro that is a cooperative venture between the antiX and former MEPIS communities

- SteamOS Steam online gaming company’s official Linux distro

- Ubuntu Kylin Ubuntu Distro designed for Mandarin Chinese as opposed to English.

- Raspbian/Raspberry Pi OS This is a Debian based distro that is standard recommended for the Raspberry Pi.

- Tails The Amnesic Incognito Live System (Tails) is a Debian-based live CD/USB with the goal of providing complete Internet anonymity for the user.

- Linux Mint Full multimedia support out of the box.

- elementaryOS elementary OS is an Ubuntu-based desktop distribution, designed to look and feel like MacOS. It also has an interesting pricing model.

- Kali Linux Security based Debian distro

- Trisquel GNU/Linux-Libre FSF recommended and Richard Stallman uses this one.

- KDE Neon KDE based desktop versioned distro based off of Ubuntu.

Red Hat Family

Red Hat Linux distribution was formed after the Debian project by Marc Ewing and Bob Young. The company went public August 11th, 1999. Red Hat source code is currently shared across three main distributions: The Fedora Project, RHEL (Red Hat Enterprise Linux), and CentOS. Currently there are ~25 Fedora based distros or as Fedora calls them “spins” – this term is unique to Fedora.

According to Red Hat this is the difference between the various Red Hat operating systems:

Fedora: The upstream project on which future Red Hat Enterprise Linux major releases are based. This is where significant operating system (OS) innovations are introduced.

CentOS Stream: CentOS Stream better connects ISV, IHV and other ecosystem developers to the OS developers of the Fedora Project–the foundation of the Fedora OS. This shortens the feedback loop and makes it easier for all voices to be heard in the creation of the next Red Hat Enterprise Linux versions.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux: A production-grade operating system that provides a more secure, supported, and flexible foundation for critical workloads and applications.

Fedora Project

The Fedora Project was started in 2003 when the Red Hat Desktop Linux product was merged with the company/community based spin off Fedora Core Linux 14. The Fedora Project’s focus was rapid development and rapid release. They would release two distributions almost yearly, with package and update support only extending back to the previous version cutting off support to viable, but from Red Hat’s point of view, outdated software. Remember their focus was rapid iteration of the project to quickly test new technologies. There is a workstation edition, a server edition, a cloud instance, as well as a container based edition Red Hat CoreOS Edition for use on Kubernetes.

- Fedora 36 was released on 05/06/22

- Fedora 35 was released on 11/02/21

- Fedora 34 was released on 05/20/21

- Fedora 33 was released on 10/27/20

- Fedora 32 was released on 04/21/20

Fedora version less that 35 are no longer supported anymore! Why is the Fedora Project so fast and so merciless on not supporting older versions? This distribution is meant for desktop users and developers who don’t mind updating rapidly, called the bleeding edge. The Fedora Project is a testing ground for technology that will eventually go into Red Hat’s enterprise Linux project, referred to as RHEL.

Red Hat Enterprise Linux–RHEL

Red Hat’s founder Mark Ewing had been an IBM employee prior to forming Red Hat. He knew something about enterprise software and more importantly enterprise profits. Red Hat began its life as a desktop Linux company. They quickly shifted their focus to compete not with Microsoft and Apple, but to take on the Unix enterprise giants of IBM, HP, Sun and AT&T. There is irony as Red Hat would be purchased by IBM 20 years later. These companies had one thing in common: they were all Unix vendors. Red Hat’s vector was to dislodge the established Unix vendors with Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL). They would successfully attack this market with entirely opensource products and running on commodity Intel x86 based processors. With Oracle also sensing a chance to capture market share along with RHEL, it announced it would port its database products to RHEL and this platform became to the go to choice for using Oracle as a database. By Oracle doing this they have all but abandoned Solaris and positioned themselves to take on Windows Server and Microsoft SQL Server.

The key to RHEL’s success in the enterprise is its long term stability. The RHEL application platform support is 5 years and paid support up to 10 years. An enterprise grade server product cannot be changing every six months like the Fedora project. Red Hat instead takes “snapshots” from the Fedora project and freezes them to produce RHEL versions. For example, RHEL 8.0 was based on Fedora 28. RHEL 9.0 was based on Fedora 34.

How successful is this strategy? By 2012 Red Hat had become the first Linux based company to make a billion dollars in a fiscal year. But this success brought about an additional serious opensource question; RHEL is licensed under the GPLv2 Free Software license, which requires that all source code for your product to be freely and openly available. That means anyone can examine, modify, and redistribute your code for their own product as well. What if someone did that? Wouldn’t they be able to ride the coat tails of Red Hat to success? The CentOS project did just that.

CentOS

By 2010 RHEL was firmly entrenched as a viable enterprise based server platform. Many customers loved the reliability of RHEL, but the two year technology freeze was to long for some people. They wanted to use RHEL but with the opportunity to update libraries and applications much quicker. The CentOS (Community ENTerprise Operating System) emerged15. The goal of this project is to use the freely available GPLv2 code of RHEL and redistribute it with their own custom modifications. Some would argue that CentOS is succeeding based on RHEL’s hard work. Until about 2014, Red Hat had a very frosty relationship with the CentOS developers–even taking them to court numerous times over trademarked Red Hat logos that had not been properly removed by CentOS developers. Their developers, like Debian, are entirely volunteer based and not backed by a company (technically since they base their work off of RHEL–they are commercially backed via Red Hat).

Eventually all of Red Hat’s copyrighted material was removed and CentOS was then in full compliance with the GPLv2 license. This made Red Hat angry because they felt that CentOS were pirates stealing their work and causing them to lose sales to enterprises that had been using RHEL but had switched to use CentOS. By 2014, Red Hat and CentOS came to terms to work together–with Red Hat offering to sell support contracts to CentOS users. Was CentOS doing anything illegal? Anything immoral? Not according to the GPLv2 and the spirit of free and opensource software.

CentOS Stream

Recently Red Hat changed CentOS’s purpose and mission. Red Hat had control of CentOS’s board of directors for a while and after IBM purchased Red Hat in 2019, Red Hat shifted CentOS to a rolling release called CentOS Stream.

From the CentOS Blog, December 2020:

CentOS Stream will also be the centerpiece of a major shift in collaboration among the CentOS Special Interest Groups (SIGs). This ensures SIGs are developing and testing against what becomes the next version of RHEL. This also provides SIGs a clear single goal, rather than having to build and test for two releases. It gives the CentOS contributor community a great deal of influence in the future of RHEL.

Oracle Linux

Oracle saw that many of their customers were paying Red Hat for operating systems licenses, buying support contracts, and running an Oracle database on top of it. Oracle wanted a piece of this pie. Oracle made a fork of RHEL’s opensource code as well, adding Oracle product code and services and redistributing it as Oracle Linux.

Oracle Linux was born in 2007 and is a fully GPL compliant OS. Oracle claims that their “Unbreakable Enterprise Kernel” is fully compatible with RHEL, and that Oracle middleware and third-party RHEL-certified applications can be installed and run unchanged. One may ask, isn’t this illegal too? Is Oracle breaking the law? Are they stealing RHEL software and reselling it? Is this piracy? Not according to the GPL - they are fully entitled to do this and thus compete with Red Hat selling support contracts on Red Hat’s created software–this is the nature of the GPL license.

SUSE Linux

- Originally a German company Linux Distro started in 1994

- SUSE is an acronym meaning: “Software und System-Entwicklung” (software and systems development)

- openSUSE Linux is a community-driven version of SUSE and released in 2004.

- In 2006 Microsoft and SUSE announce an interoperability agreement (Patent Lawsuit Protection)

- SUSE was responsible for working to port the Linux kernel to 64 bit architecture in 2000

- Major partner for deploying SAP

- Owns RancherOS – an Enterprise Kubernetes Management Platform

Intel Clear Linux

- Intel Clear Linux

- Rolling release designed by Intel with auto-updating features built into the OS.

- “Clear Linux OS is an open source, rolling release Linux distribution optimized for performance and security, from the Cloud to the Edge, designed for customization, and manageability https://clearlinux.org/.”

- Designed to work on recent Intel processors, dropping legacy support for older hardware–in order to optimize for modern cloud and OS Container based workloads like Kubernetes.

- Not focused on desktop Linux but for Cloud-based virtual machines and OS Container /assets

Gentoo Linux

- Unique Linux distro that you build from scratch based on your unique hardware, to become completely customized, fast, small, and secure.

- Uses the Portage package system.

Alpine Linux

- Alpine Linux

- Alpine uses musl as its standard C library not GNU libc, making smaller distros than standard GNU/Linux

- Designed to be minimal by design - focusing on OS Containers

- Uses OpenRC init systems

- Uses APK Alpine Package Manager

Arch Linux

Arch Linux has a different philosophy, Arch Linux defines simplicity as without unnecessary additions or modifications. It ships software as released by the original developers (upstream) with minimal distribution-specific (downstream) changes. They also have their own package manager called Pacman.

The current Steam Deck Steam OS is built using Manjaro Linux which is based on Arch and different from Ubuntu and Red Hat Oses.

Unix and the BSD Family Distros

While Linux was exploding in the mid 1990s, the AT&T lawsuit against BSD had been settled and work could resume on the BSD forks of Unix. The BSD code splintered into 3 main families or distros that are all descended from the original BSD Unix project. This leaves large pieces of BSD code compatible with each other. BSD is not Linux and technically not Unix but functions in a vary similar manner to Unix. The BSD world is not immune from forks and division.

FreeBSD

- Released in November 1994

- Essentially the inheritor of the BSD Unix code base

- Largest BSD implementation used by WhatsApp and Netflix

- No direct commercial backing, instead run by a non-profit foundation

- Legally prohibited from using the term “Unix” as the outcome of AT&T lawsuit

- Board of directors are elected and drives development, decisions, and policies

DragonFly BSD

- Fork of FreeBSD in April of 2005 by Matthew Dillon.

- Has significantly diverged from the original FreeBSD code base.

- Maintains its own package repositories

- Focused on unique techniques to handle multiprocessing in the FreeBSD kernel

- Introduced a new filesystem called HAMMER and HAMMER2

Other BSD projects

OpenBSD

- Theo de Raadt was banned/left from the NetBSD project in 1994.

- He complained that they were developing too slow and not focusing on security.

- Started a fork of NetBSD at the end of 1995

- OpenSSH, OpenNTPD, OpenSMTPD, LibreSSL, OpenBGPD, and other projects comes out of this project.

- Project is focused on radical implementations of security and safe coding practices–leveraging itself as the most secure OS.

NetBSD

- Released October of 1994 as another version of the BSD code after the lawsuit.

- Focuses on portability to run this OS on nearly every platform you can think of.

Minix 3

- Minix 3 released October of 2005.

- Since then the OS went from a teaching tool to a product being used commercially.

- Began using NetBSD userland applications for a GUI and package management.

- Intel Management Engine, contained on all modern Intel CPUs run Minix at Ring -3.

Solaris Based Unix Distros

Solaris

- Oracle killed commercial Solaris in the middle of the night September 3rd, 2017.

- Commercial Unix distribution created by Sun in the 1980s and bought by Oracle in 2010.

- Sought to merge the best of Sys V and BSD into one standard Unix.

- Ran on proprietary SPARC hardware platform

- Leader in operating system feature development

- ZFS

- Dtrace

- Zones (OS Containers/Jails)

- Network based installation – Jumpstart

- By 2006 began the process of opensourcing their technology and operating system called OpenSolaris

- In 2006 Sun had opensourced their Unix-based Solaris OS 16

- They hired Ian Murdock (founder of Debian) to oversee this project

- Project was called OpenSolaris, but was killed when Oracle purchased Sun in 2010

- Explanation of how OpenSolaris was killed and closed sourced by Oracle.

Illumos

- After the OpenSolaris project was shut down and Oracle fired most of the Solaris developers, the last version of OpenSolaris was forked into a project called Illumos17.

- Illumos is not a distro, but a reference implementation in which other OSes are based.

- OmniOS

- SmartOS released by Joyent18

- Combines the best of the BSD/Solaris technology but runs the best of Linux based desktop applications and software–especially the KVM Virtualization Platform

- Recently purchased by Samsung for their OS container technology stack called Triton and Manta.

- Releases all software, even their production cloud as open source.

Mobile Based Linux

While Android is a Linux based mobile operating system, it is different from a true Linux operating system. With Android being available and common to develop true Linux based mobile operating systems took a while to get off the ground. Starting in 2018, a movement being lead by Purism, PinePhone, and the previous work done by Ubuntu Touch, there are now Mobile Linux-based distros. These phones are the steps to move a desktop operating system to a mobile arena and all the considerations a phone and tablet have in regards to wireless, battery, and touch input.

Fifth Phase of Unix Maturity - Hard Changes to the Nature of Linux

Not since Linux Torvalds has a single developer been influential in the Linux community. Lennart Poettering is currently a developer for Red Hat19, and had previously developed PulseAudio and Avahi–network discovery demon. Lennart is mostly known for systemd. Systemd was designed as a modern replacement for SysVinit, the initial program responsible for starting all other system processes in Unix/Linux and systemd was started around 2010 and by 2015 was widely deployed amongst Linux Distros.

Why would this technology be so divisive? Well, the init system is at the root of your entire operating system and defines how the OS operates and interacts with processes. Change is difficult and the init system has been set and well known since 1983. This system is called SysVinit, after the System V AT&T Unix release. Poettering has irked many people by breaking with certain perceived Unix conventions. For him, the Unix philosophy of having small programs do one thing well is a byproduct of bygone era where computers had small amounts of storage and low processing power. He has sentimentality for the work of Thompson and Ritchie, but not if something more efficient can be created. Lennart argues, if Linux wants to be taken serious like MacOS and Windows, these changes are not only necessary but actually closer to the core Unix philosophy than what SysVinit provides.

The other major point of contention is with all the changes systemd makes to the init process. Many other pieces of software need to change as well. Linux has always been about the freedom to choose your software, but systemd has made fundamental choices forcing fundamental changes to the structure of how software interacts with the Linux kernel. For example, the GNOME desktop developers have chosen to integrate their software with systemd directly. This means that you have no choice but to use systemd instead of SysVinit if you want to use the GNOME desktop. You are basically locked into using GNOME as a Desktop environment in this case, which some would argue is progress and some would argue as captivity. Note that BSD still uses SysVinit; systemd is a pure Linux-ism and not compatible with BSD.

You need to give Lennart credit for convincing all major Linux distros to adopt systemd as their init system. Lennart convinced his management at Red Hat to take a chance on his technology, and now most of the industry followed suit 6+ years after he first released systemd. That is not an easy accomplishment if you think about it.

The first company to adopt systemd was Red Hat. Debian was the last holdout and they had a spirited debate, which led to a number of resignations and a split within the community over the issue. Some Debian developers left and went on to form a distro called Devuan–which is focused on removing all systemd and udev dependencies from a Debian based Linux distro.

In its defense, systemd has many nice and actually new and needed features for Linux. Lennart is updating pieces of Linux that haven’t been touched in decades. He even wrote a 21 part defense of systemd on his website. We will talk more on the technical aspects of systemd in the chapter 11. By using systemd, Linux distros make another fundamental choice, to break with Unix based system compatibility. Systemd is entirely Linux centric and draws a sharp dividing line between Linux and Unix/BSD based distros.

Sixth Phase of Linux Maturity - OpenSource is not a business model

As the story moves into the year of 2019, we begin to see the issue of opensource software and the nature of commercial companies come into conflict. To complicate this, these companies are wide-spread and heavily used across the industry and these companies happen to be Venture Capital funded. These companies, which had relied on opensource software as their business model, have now come into competition directly with large Cloud vendors, mostly Amazon Web Services. These Cloud companies offer cloud-hosted versions of opensource products (legally and correctly) and because of the opensource licenses chosen, don’t need to contribute any code or money back to the original product. In some cases the number of developers working on a forked version of a software for the major Cloud providers, vastly out number the original company’s developer workforce. What can these companies do? They decided on a licensing vector of attack against the cloud providers.

- MongoDB

- Confluent

- Redis

- CockroachDB

- Amazon vs Elastic